The Tell

Two words that reveal you don’t understand positioning: “brand positioning.”

This isn’t pedantry. It’s diagnostic. The phrase inverts causality, conflates two distinct phenomena, and reveals a conceptual confusion that has cost companies billions in misdirected strategy work.

When someone says “brand positioning,” they’re typically doing one of three things: using one word to do two jobs, confusing cause with effect, or revealing they learned positioning from people who learned it wrong.

Let me untangle this.

The Distinction Most Practitioners Miss

Position is the concept you own in someone’s head — proven through decisions, not claimed through words. It’s a noun. Mental territory. The anchor.

Brand is the set of associations, expectations, and reputation that accumulates over time through interactions with your business. It’s perception. The structure that forms around the anchor.

These are not the same thing. They operate on different timescales, through different mechanisms, and are controlled by different parties.

Position is a strategic choice you make. Brand is a verdict the market renders.

Volvo’s position is Safety. Their brand (Swedish engineering, family-oriented, boxy design, practical premium) clusters around that core concept. Every association reinforces the anchor. But Safety came first. Safety directed the decisions. Safety is what they chose to prove through every product, feature, and trade-off. The brand associations accumulated afterward, as the market watched those decisions compound over decades.

You don’t position a brand. You establish a position. Then the brand forms around it through consistent decisions over time.

The Causality Problem

Here’s the logical issue no one addresses:

If brand is the accumulated perception that forms after customers watch your decisions, how can it also be the thing directing those decisions?

Effect cannot be cause.

What directs decisions is position, the concept you commit to proving. Third Place. Belong. Safety. Future.

What results from decisions is brand, the perception that accumulates in the market’s mind after years of watching you act.

Position is cause. Brand is effect.

The phrase “brand positioning” collapses this sequence into a single activity, as if you could work on perception directly. You can’t. You can only work on the decisions that shape perception. The market handles the rest.

Why the Phrase Exists (And Who Benefits)

“Brand positioning” emerged as branding became the dominant paradigm in marketing. The term suggested positioning was a branding exercise. Something you do after brand identity work is complete.

That’s the opposite of how the original theorists conceived it. Al Ries, who coined the concept with Jack Trout, was explicit: “Positioning is not what you do to a product. Positioning is what you do to the mind of the prospect.” The mechanism was always about mental territory. Claiming a concept in someone’s head before competitors could.

But the term drifted. “Brand positioning” allowed agencies to sell “brand strategy” and “positioning work” as different engagements. It allowed companies to think they could fix “brand perception” without changing operational reality. It allowed marketing departments to create positioning decks while the business made contradictory decisions.

The phrase serves commercial interests. It does not serve strategic clarity.

Why Explicit Claims Fail

“Brand positioning” implies you can shape perception (brand) by crafting the right message (positioning). That’s not just backwards. It fails for a specific psychological reason. Explicit claims trigger defence mechanisms.

The moment you say “We’re innovative,” you activate what researchers call the Persuasion Knowledge Model, and customers recognize the marketing tactic. You trigger Psychological Reactance; they resist being told what to think. You create Manipulative Intent Inference; they perceive you’re serving your interests, not theirs.

These defences force System 2 processing: slow, analytical, skeptical thinking that evaluates claims consciously. Explicit claims build only declarative knowledge: “I know Brand X says they’re innovative.” This knowledge is weak. It requires conscious evaluation at every purchase decision. It can be easily countered by competitor claims.

This is why most “positioning work” fails. It’s built on explicit claims that activate the exact defences that prevent the position from taking hold.

Why Implicit Proof Works

Implicit positioning bypasses all of this. When every decision proves a concept without stating it, customers generate their own inferences. Self-generated conclusions are more persuasive than stated benefits — people’s own conclusions they drawn by themselves.

Implicit proof works through System 1: automatic, emotional, instant thinking that operates below conscious awareness. It builds procedural knowledge: “When I need this category, I automatically think Brand X.” This knowledge is strong. It operates as automatic behavioural scripts that activate without deliberation. It cannot be easily disrupted because it functions below awareness.

The mechanism is Hebbian learning: neurons that fire together wire together. Every consistent experience strengthens specific neural pathways through repeated co-activation. After sufficient repetitions, the brand triggers the concept automatically without conscious evaluation. The position exists in neural wiring, not conscious thoughts.

Volvo doesn’t claim safety. Every product decision proves it. Customers conclude “safety” for themselves after watching decades of consistent choices. That self-generated inference is more durable than any tagline.

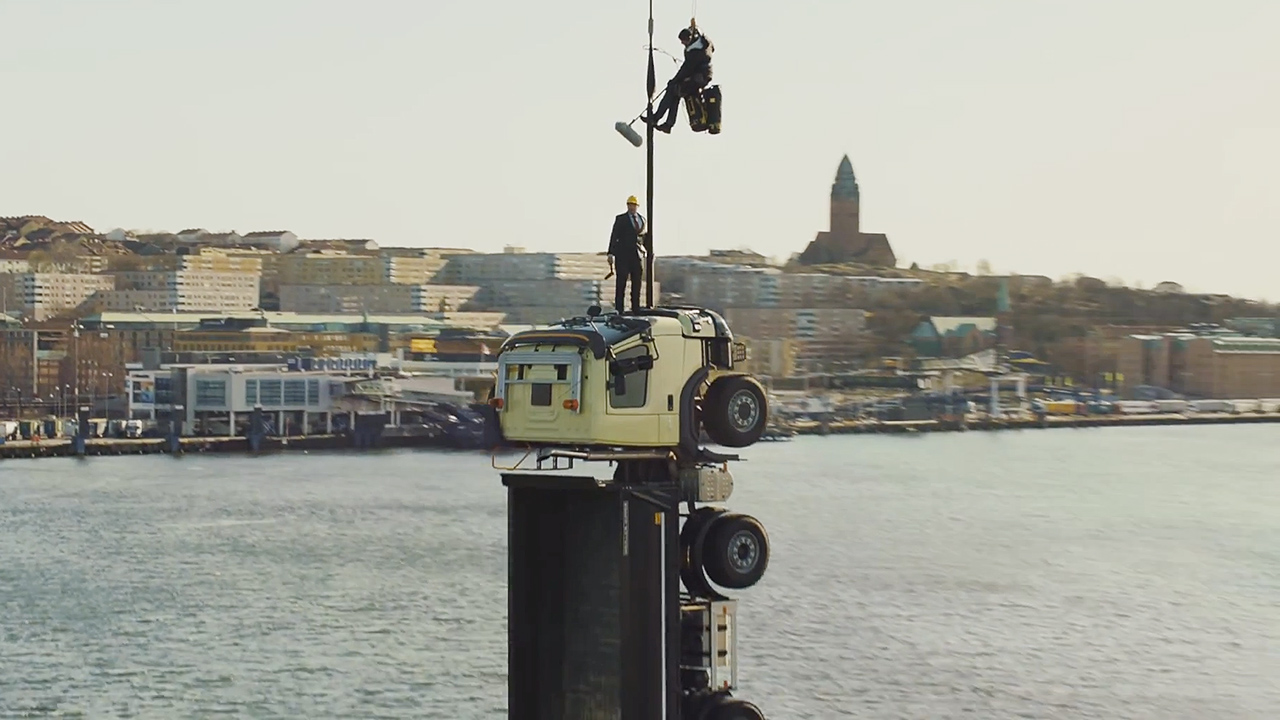

The Burj Khalifa doesn’t claim eminence. It proves it. That’s the standard.

The Oldsmobile Lesson

Roger Martin documented one of the clearest cases of this failure.

GM spent years trying to “reposition” Oldsmobile through campaigns claiming “This is not your father’s Oldsmobile.” The explicit message: we’re young, we’re different, we’ve changed. The brand died anyway.

Martin’s verdict: “You can’t stand for something that you aren’t.”

The failure wasn’t the advertising. The advertising was fine. The failure was attempting to claim through messaging what couldn’t be proven through product and experience. The cars hadn’t changed. The dealership experience hadn’t changed. The customer base hadn’t changed. Only the words had changed.

Explicit claims without implicit proof don’t reposition anything. They just make the gap between claim and reality more visible.

The Overloaded Word Problem

Part of the confusion: “brand” has become the most overworked word in business.

Watch how it’s used:

- “Our brand directs our business decisions” (brand as strategy)

- “We need to protect our brand” (brand as reputation)

- “Let’s update the brand” (brand as visual identity)

- “The brand experience needs work” (brand as customer journey)

- “Brand is our culture” (brand as internal identity)

- “We need a brand positioning” (brand as… everything)

When one word does six jobs, it does none of them well.

I recently watched a LinkedIn thread where two smart strategists argued past each other for days. One insisted “brand directs the business” (citing Starbucks’ Third Place, Airbnb’s Belong Anywhere). The other insisted, “Business decisions determine brand.” They were both right. They were using “brand” to mean two different things.

What the first called “brand directing business” was actually the position; the concept that shaped decisions. What the second, called “business decisions determine brand,” was the consequence; perception accumulating from those decisions. The word “brand” isn’t big enough to hold both cause and effect. But we keep asking it to.

What Practitioners Actually Get Wrong

After years of working with companies on positioning, I’ve identified the consistent errors:

1. Treating positioning as a communication exercise

Most “positioning work” produces messaging frameworks, brand pyramids, positioning statements, and tone-of-voice guidelines. None of this is positioning. It’s documentation. Real positioning shows up in capital allocation, product roadmap choices, what you refuse to do, organizational structure, and where you hire and fire. These are P&L decisions. Business strategy decisions. The deck is an artifact. The decisions are the position.

2. Confusing positioning statement with market position

A positioning statement is how you wish to be perceived. A position is how you are actually perceived. These are often completely different. The only way to know your actual position is to watch what customers do automatically, not what they say when asked. Surveys measure declarative knowledge (what people consciously report). Real positions are built through procedural knowledge (automatic behavioural patterns). Different mechanisms entirely.

3. Attempting to position through messaging what can’t be delivered through experience

You cannot claim what you cannot prove. If your product is complex, you cannot position it as “simple” through clever copy. If your service is slow, you cannot position yourself as “fast” through brand messaging. The market watches your decisions, not your deck. Claims without proof don’t create positions. They create credibility gaps.

4. Skipping the foundation

Companies want Level 4 outcomes (owning a concept) without building Levels 1-3 (framing, execution, structural embedding). Positioning takes years to establish; typically, five to ten years of consistent business decisions before a concept becomes truly owned. You cannot workshop your way to a position in a quarter. You can only choose a direction and start proving it.

5. Using “brand positioning” as a term

The phrase itself reveals the confusion. Stop using it.

The Practical Implication

Here’s what this means for your work:

Position is a choice. What concept will you own? What noun? Not an adjective (innovative, trusted, fast). A noun (innovation, trust, speed). Nouns own territory. Adjectives describe it. Once Volvo owns “safety,” competitors can only claim to be “safer than,” an inherently weaker position that acknowledges Volvo’s leadership.

Decisions are proof. Every product feature, pricing choice, partnership, channel decision, and rejection either proves or dilutes your position. The market doesn’t read your strategy deck. It watches your resource allocation. If your positioning says “simplicity” but your product roadmap adds complexity, the market concludes that your product is complex. Actions speak. Words trigger defences.

Brand is a verdict. You don’t control it. You influence it through consistent proof over time. The brand that forms is the market’s conclusion about what you actually are, based on what you actually did. Not what you said. Not what you intended. What you proved.

Consistency compounds. Every decision that proves the same concept strengthens the neural pathway. Competing decisions create competing patterns that weaken brand strength. This is why focus matters. This is why sacrifice matters. This is why saying no matters. You cannot own everything. You can only own what you consistently prove.

The Test

Remove every piece of marketing copy. Delete every tagline. Strip away every claim. What’s left?

If positioning is real, you see a pattern of decisions all pointing to the same concept without stating it. Product choices, pricing, partnerships, design — all proving something implicitly.

If positioning is fake, you find confusion. The only thing holding the “position” together was the words used to describe it.

Patagonia without messaging still proves environmental commitment. In-N-Out without taglines still proves fresh quality. Costco without claims still proves value. The pattern survives the removal of words.

That’s the test.

The Directive

Stop saying “brand positioning.”

Say positioning. Then make decisions that prove it.

The brand will follow, or it won’t.

The market decides.

Your job is to give it no other conclusion to reach.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.