Most positioning conversations happen in conference rooms.

Executives debate.

Consultants facilitate.

Post-its accumulate.

Everyone leaves with an opinion about what the company’s position should be.

Here’s the problem: position isn’t an opinion.

Position isn’t what you decide in a workshop. It isn’t what you write on a slide. It isn’t what your leadership team agrees sounds good.

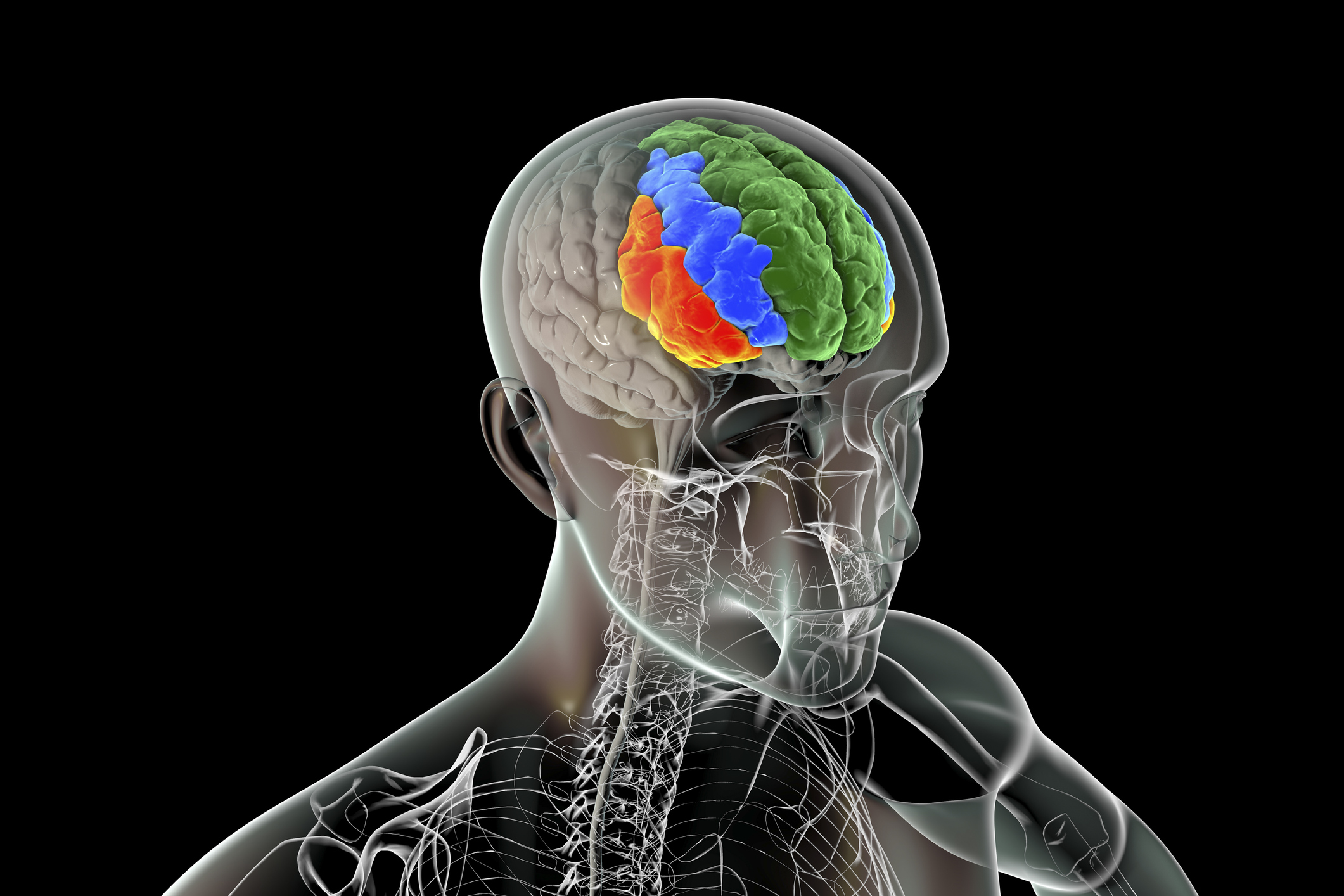

Position is neural architecture. Physical wiring in your customers’ brains. It either exists there or it doesn’t. And your opinion about it is irrelevant.

This distinction matters because it changes everything about how you build, measure, and defend positioning. Most companies are playing the wrong game entirely.

The Workshop Delusion

Watch how most companies approach positioning. They gather stakeholders. They discuss target audiences. They craft value propositions. They wordsmith taglines. They align on messaging frameworks.

Then they wonder why nothing changes.

Nothing changes because they’ve been working on articulation while ignoring architecture. They’ve perfected how they describe something that doesn’t exist.

A position isn’t created in your conference room. A position is created through consistent experiences that physically rewire how customers’ brains process your category.

You can have the most elegant positioning statement ever written. If customers haven’t experienced proof of that position repeatedly over time, you have words. Not position.

How Positioning Actually Works: The Neural Mechanism

Positioning operates through a principle called Hebbian learning. The summary: neurons that fire together, wire together.

When customers repeatedly experience your brand associated with a specific concept, the neural pathways processing these stimuli become physically connected. Synapses strengthen. After enough repetitions, activation of one stimulus automatically triggers the other.

This isn’t a metaphor. It’s neurobiology.

The process has distinct phases:

Phase 1: Initial Exposure. Customer experiences your brand and a concept as separate events. No automatic association exists. The brain processes them independently.

Phase 2: Repeated Co-activation. Customer repeatedly experiences your brand, proving the concept. Each instance fires both neural pathways simultaneously. Synaptic connections form. Association builds but still requires conscious activation.

Phase 3: Pathway Consolidation. After many repetitions (dozens to hundreds, depending on consistency), neural pathways become physically wired together. Association becomes automatic. Your brand activates the concept without conscious thought.

Phase 4: Automaticity. Your brand triggers the concept before conscious evaluation can occur. Customers cannot separate the brand from the concept even if they try. Association operates faster than conscious processing.

The position now exists in neural structure, not conscious memory.

Think about coffee. The first time you drink it, taste and caffeine are processed separately. After weeks, the smell starts triggering alertness before caffeine absorption. After months, you cannot smell coffee without feeling more alert. The pharmacological effect and learned association become neurologically indistinguishable.

That’s what positioning is. Not what you claim. What you’ve wired.

Two Types of Knowledge: Why Most Positioning Is Weak

Human memory operates through two fundamentally different systems. Understanding this distinction explains why most positioning fails.

Declarative Knowledge is conscious and explicit. You can articulate it. “I know Brand X says they’re innovative.” It’s stored as facts you can retrieve and evaluate.

This type of knowledge is weak for positioning because:

- Competitors can counter with their own claims

- Requires continuous reinforcement to maintain

- Forces conscious evaluation at every purchase

- Susceptible to forgetting

- Customers must justify their choice rationally

Procedural Knowledge operates below awareness. It manifests as automatic patterns. “When I need this category, I automatically think Brand X.” You can’t articulate why. It just happens.

This type of knowledge is strong for positioning because:

- Cannot be easily disrupted by competitor claims

- Operates automatically during decisions

- Persists without continuous marketing investment

- Bypasses conscious evaluation entirely

- Customers choose without needing to justify

The transformation matters:

Initial exposures create declarative knowledge → Repeated consistent experiences strengthen associations → Neurological pathway consolidation occurs → Procedural knowledge forms

Once procedural knowledge is established, it can only be disrupted by inconsistent experiences that break the pattern, category disruption that changes the decision context, extended absence from the market, or a fundamental failure of the core association.

Traditional positioning focuses on declarative knowledge, what customers can consciously state about you. Effective positioning builds procedural knowledge that customers automatically use when a category need arises.

The Proof: When Scientists Removed the Neural Architecture

The most compelling evidence comes from brain research you’ve probably heard about but never applied.

McClure et al. conducted the famous Coke vs. Pepsi study. When subjects didn’t know which drink they were tasting, preference was roughly split. In a blind taste test, Pepsi often won slightly.

But when subjects knew which brand they were drinking, something specific happened in their brains. Knowledge of Coca-Cola activated the hippocampus (memory recall) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (emotion-modified behaviour). Brand associations literally overrode sensory perception.

The researchers’ conclusion: brand knowledge had “insinuated itself into the nervous systems” of consumers.

This isn’t a preference.

This is physical architecture.

The follow-up study by Koenigs and Tranel proved causation. They studied patients with damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the brain region that processes brand associations.

Result: patients with this damage showed no brand preference bias whatsoever.

Read that again. When the neural architecture was physically absent, the preference disappeared completely. The position wasn’t an opinion held by those patients. It was wiring they lacked.

This is why debates about positioning are often pointless. Your opinion about what position you should own doesn’t matter. What matters is what you’ve wired into customer brains through consistent proof over time.

Why Explicit Claims Fail: The Defence Mechanism Problem

When you explicitly claim a position, “We’re the most innovative” or “We’re committed to quality,” something specific happens in customer brains: defence mechanisms activate.

Research identifies three primary mechanisms:

Persuasion Knowledge Model. Throughout life, consumers develop elaborate knowledge about marketing tactics. When they recognize a persuasion attempt, they shift from accepting information to evaluating it skeptically. They activate what researchers call “schemer schemas,” lay theories about marketer manipulation.

Psychological Reactance. Explicit directives threaten perceived freedom. When you tell customers what to think about you, they resist. The stronger the claim, the stronger the resistance.

Manipulative Intent Inference. Customers continuously assess whether marketers act in their own self-interest or in the customer’s interest. Explicit claims obviously serve advertiser interests. “Of course, they’d say they’re innovative; they want my money.” This inference triggers skepticism.

These defences force System 2 processing — slow, analytical, skeptical thinking that evaluates claims consciously. This is the opposite of what strong positioning requires.

Explicit claims build only declarative knowledge. “I know Brand X says they’re premium.” This knowledge is weak because it requires conscious evaluation at every purchase and can be easily countered by competitor claims.

Why Implicit Proof Works: Self-Generated Inferences

Implicit positioning bypasses defence mechanisms entirely.

When every decision proves a concept without stating it, customers generate their own inferences. They conclude things for themselves rather than being told.

This matters because self-generated conclusions are more persuasive than stated benefits. When customers draw their own inference, “Nike really backs their athletes, they must be serious about performance,” that conclusion feels like their insight, not your marketing.

Research by Briñol, McCaslin, and Petty found that self-generated arguments are especially strong because people are less resistant to their own thoughts. Walster and Festinger demonstrated that people are more persuaded when they “overhear” a message than when it is explicitly addressed to them.

Implicit positioning works through System 1, automatic, emotional, and instant processing that operates below conscious awareness. It builds procedural knowledge: “When I need this category, I automatically think Brand X.”

This is strong because it operates as automatic behavioural scripts that activate without deliberation and cannot be easily disrupted since they function below awareness.

The positioning paradox: explicitly claiming a position weakens it. Implicitly proving a position strengthens it.

The Consistency Requirement: Why Inconsistency Destroys

Hebbian learning requires consistent co-activation. Inconsistent experiences create competing neural patterns. Multiple competing patterns weaken overall association strength. This means inconsistency doesn’t just fail to build positioning, it actively destroys existing positioning.

Research on “catastrophic interference” shows that rapid learning of new information inconsistent with prior knowledge disrupts previously established representations. Elizabeth Loftus’s misinformation effect research demonstrates that contradictory information doesn’t just add confusion; it physically alters original memory.

The case studies are stark.

Gap’s 2010 logo change lasted six days before reverting, at an estimated cost of $100 million. The new logo generated 14,000+ parody versions and immediate backlash. It broke the visual trigger for existing neural pathways.

Tropicana’s 2009 redesign removed the iconic orange-with-straw image that served as a neural retrieval cue. Result: 20% sales drop within two months and $30 million in lost sales in the first month alone. Customers literally couldn’t recognize the product because visual patterns were disrupted.

One major inconsistency can undo years of consistent association-building. This is why positioning is measured in decades, not quarters. You cannot accelerate neural pathway formation through more aggressive messaging. You can only strengthen it through more consistent experiences.

Costly Signals vs. Cheap Talk

There’s a fundamental distinction in how humans evaluate information.

Cheap talk is words anyone can produce at minimal cost. Claims that require no sacrifice. “We’re the best.” “We’re committed to quality.” Anyone can say these things. They’re linguistically easy to produce and strategically useless to believe.

Costly signals are actions that require significant investment. Decisions that involve real sacrifice. Behaviours anyone can observe and verify.

Nike signing Michael Jordan for $2.5 million when average NBA shoe deals were a fraction of that? Costly signal. Paying his NBA fines rather than asking him to comply with uniform rules? Costly signal. Building R&D infrastructure to innovate continuously? Costly signal.

These decisions would be irrational if commitment weren’t genuine. That’s what makes them credible.

Patagonia’s donation of profits to environmental causes is a costly signal. Saying “we care about the environment” in marketing is cheap talk. In-N-Out refusing to expand nationally and compromise quality is a costly signal. Claiming “fresh ingredients” is cheap talk.

Cheap talk triggers skepticism and defence mechanisms. Costly signals bypass skepticism and build credibility.

Competitors can easily counter explicit claims with their own explicit claims. That’s cheap talk versus cheap talk. Competitors cannot easily counter implicit proof by making costly decisions without incurring the same costs, often a strategic impossibility.

The Implicit Positioning Test

Here’s a diagnostic that separates real positions from marketing fantasies:

Remove all marketing copy. Delete every tagline. Strip away every claim. Take away all the words.

What’s left?

If positioning is real, you see a pattern of decisions pointing to the same concept without stating it. Product choices, pricing, partnerships, and design all implicitly convey something.

If positioning is fake, confusion results. The only thing holding the position together was the words used to describe it.

Patagonia, without messaging, still proves environmental commitment through their business model. Tesla, without advertising, still proves the future through every product decision. In-N-Out, without taglines, still proves fresh quality through their operational constraints.

These positions survive because structural decisions prove them. The words are exhaust fumes from an engine that runs without them. Your position should pass the same test.

What This Means for Your Business

If you’re reading this hoping for messaging inspiration, you’ve missed the point. The lesson isn’t “craft better claims.” It’s “build proof worth compressing.”

Most businesses don’t have a positioning problem. They have a proof problem. They’ve perfected articulation. Website copy is tight. The value proposition is clear. None of it matters because there’s no structural foundation underneath.

You cannot frame your way into owning a concept. You can only frame a concept you already own through accumulated decisions.

Diagnostic questions:

What concept do your decisions prove? Not what you claim. Not what you want to own. What do your actual choices (product features, pricing, partnerships, hires, resource allocation) prove about what you actually are? Audit your last 50 significant decisions. What pattern emerges? If no pattern exists, you don’t have positioning. You have messaging.

Would your position survive without words? Run the implicit positioning test. Strip away marketing copy, taglines, and claims. Does a clear pattern emerge from decisions alone? Or does confusion reveal that position exists only in language?

Are you building procedural or declarative knowledge? Declarative knowledge is conscious awareness of your claims. Procedural knowledge is an automatic association with your concept. Track how customers describe you without prompting. Do they use your language? Or do they articulate the concept in their own words because they’ve experienced it directly?

What costly signals have you sent? Not what you’ve said, what sacrifices have you made that would be irrational unless commitment were genuine? These are the only signals that build credibility.

What would a competitor need to do to copy you? If the answer is “run similar ads” or “use our messaging framework,” you don’t have a position. You have a claim. Real positioning requires structural replication that takes years and significant investment.

The Reality

Position is not an opinion you hold. It’s the architecture you build.

The position exists in physical neural wiring, not conscious thoughts. It’s procedural knowledge that operates below awareness, activates faster than conscious thought, and cannot be easily disrupted by competitor claims.

You cannot vote on this in a workshop. You cannot decide it in a strategy session. You cannot declare it in a press release.

You can only build it through consistent proof over time. Decisions that prove the same concept. Costly signals that couldn’t exist if commitment weren’t real. Experiences that wire the brand and concept together in customers’ minds, making them inseparable.

Everything else is noise.

The question isn’t what position you want to own. The question is what position your decisions have already built (or failed to build) in the minds of people who matter.

That’s not an opinion.

That’s neuroscience.

And it doesn’t care what your workshop decided.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.