The highest-IQ people aren’t the wealthiest. They never have been.

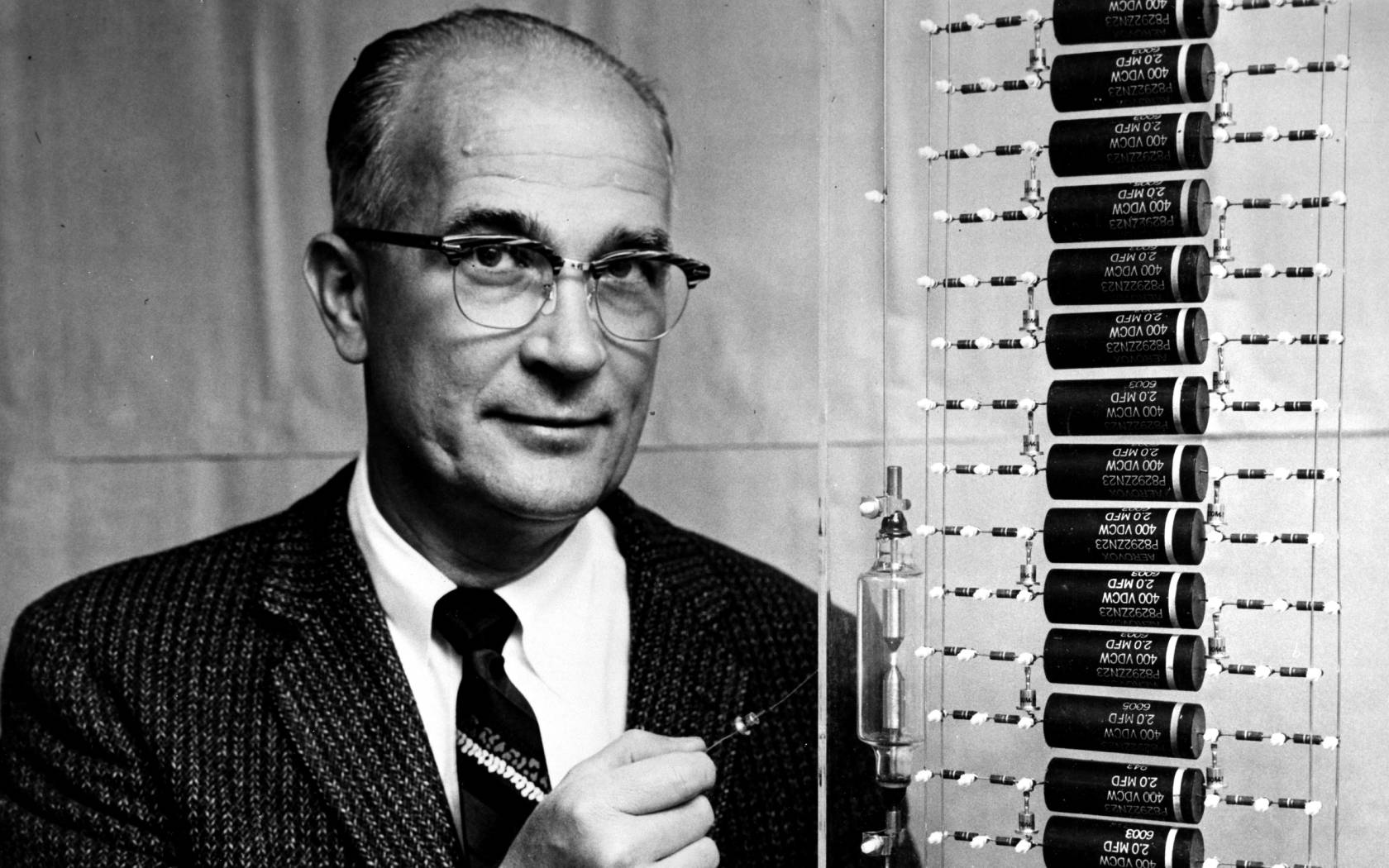

The Terman Study tracked 1,528 children with IQs above 135 for 74 years — one of the longest longitudinal studies ever conducted. The conclusion surprised everyone: these “geniuses” were no more successful in adulthood than children randomly selected from similar socioeconomic backgrounds. Meanwhile, two children rejected from the study for not scoring high enough, Luis Alvarez and William Shockley, went on to win Nobel Prizes.

Swedish register data adds another wrinkle. Above €60,000 in annual wages, cognitive ability ceases to be a predictor of income. Stranger still: the top 1% of earners actually score slightly lower on cognitive tests than those just below them.

Research shows IQ explains only 2.4% of the variance in net worth. So why do we keep acting like intelligence is the bottleneck?

Bryan Johnson recently tweeted that “the cost of manufacturing and distributing intelligence is headed to zero.” He’s right. But he’s describing the supply side. The question nobody’s asking is what happens on the demand side. What becomes scarce when everyone has access to infinite cognitive horsepower?

The conventional answers cluster around judgment, taste, trust, and authenticity. These aren’t wrong. But they’re incomplete.

The real bottleneck (the one that will separate those who thrive from those who struggle) is more specific and more uncomfortable: the human capacity to unlearn.

When Intelligence Commoditizes, Learning Becomes Table Stakes

Every major technological transition follows a consistent pattern: when a capability becomes abundant, value migrates to its complements.

The printing press made text reproduction cheap. What became scarce wasn’t access to books; it was authoritative interpretation. The Church’s monopoly on scriptural meaning collapsed not because people suddenly had Bibles, but because Luther could offer a competing interpretation to mass audiences. The bottleneck shifted from copying to curation.

Computing power commoditized across the 1990s and 2000s. Value migrated up the stack, from hardware to software, then to data, then to platforms commanding network effects. Dell became a commodity; Google became a monopoly. The bottleneck shifted from processing to organizing.

The internet made distribution essentially free. Value migrated to what couldn’t be distributed: trust, reputation, verified quality. Any blog could publish; few could command attention. The bottleneck shifted from reach to credibility.

Now, intelligence itself is commoditizing. AI models can reason, write, code, analyze, and synthesize across virtually every domain. Access to cognitive capability is no longer scarce. A solopreneur with Claude has analytical firepower that would have required a team of consultants a decade ago.

The obvious conclusion is that learning becomes table stakes. If everyone can access infinite intelligence, then knowing things loses its premium. This is true, but it misses the harder problem.

Learning is actually getting easier. AI tutors can explain any concept, at any level, with infinite patience. The friction of acquiring new knowledge is collapsing. You can learn faster now than at any point in human history.

But the ability to unlearn — to abandon knowledge, frameworks, identities, and instincts that are no longer serving you — remains as friction-filled as ever. And that friction is about to become the primary constraint on human adaptation.

Why Unlearning Is Harder Than Learning

Consider what happens when you learn something.

You invest time and cognitive effort. You practice until the knowledge becomes automatic. You build identity around your expertise. You signal that expertise to others and receive social validation. You make career decisions based on that knowledge. You hire people, structure teams, and design processes around it.

Learning creates what economists call “sunk costs” and what psychologists call “commitment.” The more you’ve invested in knowing something, the more painful it becomes to admit that knowledge is no longer valuable — or worse, that it’s actively holding you back.

Now consider what unlearning requires.

You must first recognize that something you know is wrong or obsolete, which means overcoming confirmation bias that filters information to match existing beliefs. You must then accept that your investment was, in some sense, wasted, which means overcoming loss aversion that makes us value what we have over what we might gain. You must abandon frameworks that still technically work, just suboptimally, which is much harder than abandoning things that have completely failed. And you must do all this while your identity, status, and often livelihood are tied to the very expertise you’re being asked to release.

Learning adds to what you have. Unlearning subtracts from who you are.

This asymmetry explains a pattern that recurs throughout business history: incumbents don’t fail because they can’t learn new things. They fail because they can’t unlearn old things fast enough.

The Graveyard of Companies That Couldn’t Unlearn

Kodak didn’t fail because it couldn’t learn about digital photography. Kodak invented the digital camera in 1975. Steven Sasson, the engineer who built it, was told by management to keep it quiet because it would cannibalize film sales. The company knew about the technology two decades before it disrupted them. What they couldn’t do was unlearn the mental model that said their business was selling film. By the time they tried, the sunk costs (manufacturing infrastructure, distribution relationships, profit margin expectations, organizational structure) were too deep to abandon.

Blockbuster didn’t fail because it couldn’t learn about streaming. Blockbuster was offered Netflix for $50 million in 2000 and turned it down. More importantly, Blockbuster launched both a streaming service and a mail-order DVD business. What they couldn’t unlearn was the model that said retail locations and late fees were the business. Late fees alone generated $800 million annually. Unlearning that revenue stream (even to save the company) proved psychologically and organizationally impossible.

Encyclopedia Britannica didn’t fail because it couldn’t learn about digital reference. They launched a digital version. What they couldn’t unlearn was the model that said authority comes from scarcity and curation. Wikipedia’s open, crowdsourced model wasn’t just a different technology; it was an inversion of everything Britannica knew about how knowledge should work. Their expertise in “how encyclopedias are made” was precisely what prevented them from making the new kind.

Nokia didn’t fail because it couldn’t learn about smartphones. Nokia was the world’s largest phone manufacturer and had more resources than Apple when the iPhone launched. What they couldn’t unlearn was the mental model that said phones are hardware products differentiated by form factor, battery life, and durability. The shift to software platforms as the locus of value required abandoning everything Nokia knew about how to compete.

The pattern is consistent: what kills organizations isn’t ignorance of the new. It’s attachment to the old.

The Mechanism: Why Expertise Becomes Liability

There’s a specific mechanism that explains why deep expertise becomes a liability during paradigm shifts.

When you become an expert in a domain, you don’t just accumulate facts. You develop what cognitive scientists call “chunking,” the ability to perceive patterns and make decisions without conscious deliberation. A chess grandmaster doesn’t evaluate each piece individually; they see board positions as unified patterns. A radiologist doesn’t examine each pixel; they perceive diagnostic gestures.

This chunking is what makes experts fast and effective. But it’s also what makes them rigid. The patterns are encoded below the level of conscious awareness. You can’t easily “unchunk” your perception. You can’t unsee what expertise has trained you to see.

When the underlying domain shifts, this becomes a problem. The expert’s chunked patterns, the very thing that made them effective, now point them toward outdated conclusions. And because the patterns operate below conscious awareness, the expert doesn’t experience themselves as using outdated knowledge. They experience themselves as “just seeing things correctly.”

Beginners, paradoxically, sometimes adapt faster precisely because they haven’t chunked the old patterns. They’re slower and less effective within the old paradigm. But they don’t have perceptual habits to unlearn when the paradigm shifts.

This explains the counterintuitive finding from AI productivity research: lower performers gain more from AI assistance than high performers. Novice customer service agents saw a 35% increase in productivity; experts saw almost none. Junior developers using GitHub Copilot completed tasks 35-39% faster; senior developers improved by only 8-16%.

The conventional interpretation is that AI “levels the playing field” by giving novices access to expertise they lack. But there’s another interpretation: experts are slower to integrate AI assistance because they have to unlearn existing workflows, while novices have nothing to unlearn.

Why AI Accelerates the Unlearning Crisis

Every previous technological transition gave incumbents time. Kodak had nearly thirty years between the invention of digital photography and the collapse of its film business. Blockbuster had a decade between DVD-by-mail and streaming dominance. The printing press took centuries to fully transform European society.

AI is different in at least three ways that compress the timeline for unlearning.

First, the pace of capability improvement is unprecedented. The difference between GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 was roughly eighteen months. The difference between Claude 2 and Claude 3.5 was less than a year. Capabilities that don’t exist today may be commoditized within quarters, not decades. Whatever expertise you’re accumulating right now may have a dramatically shorter shelf life than expertise accumulated a generation ago.

Second, AI creates capability abundance across all domains simultaneously. Previous technological transitions disrupted specific industries while leaving others untouched. Digital photography disrupted Kodak, but not law firms. The internet disrupted retail but not restaurants. AI affects every domain that involves cognitive work, which is nearly every domain. There’s no “safe” industry where old expertise will remain valuable indefinitely.

Third, AI inverts the relationship between knowledge and capability. In the pre-AI world, capability was upstream of knowledge: you had to know things to do things. In the AI world, capability increasingly follows intention: you have to know what you want, and then AI can help you do it. This means the type of knowledge that matters is shifting — from knowing how to execute to knowing what to execute on. Most existing expertise is execution-focused. Unlearning that orientation is a different challenge from unlearning specific facts or skills.

The half-life of expertise is collapsing. The pace at which you need to unlearn is accelerating. And the depth of unlearning required (not just skills, but fundamental orientations toward knowledge itself) is increasing.

The Identity Problem

If unlearning were merely a cognitive challenge, it would be difficult but manageable. You could develop exercises, frameworks, and disciplines for updating your mental models. But unlearning isn’t merely cognitive. It’s existential.

When someone asks what you do, you answer with a noun. “I’m an accountant.” “I’m a developer.” “I’m a strategist.” These nouns aren’t just job descriptions. They’re identity claims. They tell you who you are, what tribe you belong to, and how you matter.

When AI commoditizes the doing of your noun, it threatens more than your income. It threatens your sense of self.

This is why the conversation about AI job displacement often misses the point. The economic question, “Will people be able to find new jobs?” is probably yes, at least in the medium term. The psychological question, “Will people be able to release their attachment to identities built over decades?” is much harder.

Consider a senior developer who spent 20 years mastering a specific programming language, an architectural pattern, and a set of best practices. AI coding assistants are now generating functional code that doesn’t follow their best practices but nonetheless works. The developer can see that the code is effective. But accepting this means accepting that twenty years of identity-forming expertise can be matched by a few well-crafted prompts.

The rational response is to shift focus, to become the person who knows which problems are worth solving, not the person who knows how to solve them. But that requires unlearning an identity, not just a skill set. And identities don’t unlearn easily.

The people most at risk aren’t those with the least expertise. They’re those with the most, and the most identity fused with that expertise.

What This Means for Organizations

Individual unlearning is hard. Organizational unlearning is harder.

Organizations encode learning in structures, processes, incentives, and culture. When a company “learns” that a certain approach works, it doesn’t just remember this fact; it builds systems around it. Hiring criteria, performance reviews, promotion paths, meeting structures, communication norms, and strategic planning processes all crystallize around what the organization knows.

This crystallization is what makes organizations effective. But it’s also what makes them rigid. To unlearn at an organizational level, you don’t just need individuals to change their minds; you need the organization to change its mind. You need to rebuild systems that have self-reinforcing dynamics.

Tyler Cowen makes this point vividly: “Just try going to a mid-tier state university and sit down with the committee designed to develop a plan for using artificial intelligence in the curriculum. And then come back to me and tell me how that went, and then we’ll talk about bottlenecks.”

The bottleneck isn’t that the committee doesn’t know about AI. It’s that the committee’s entire way of operating, its pace, its governance structure, its stakeholder balancing, its risk orientation, was learned over decades and cannot be quickly unlearned. The committee doesn’t need more intelligence. It needs less institutional memory.

This suggests that organizational age and success may become liabilities in ways they weren’t before. Young organizations have less to unlearn. Failed organizations have been forced to unlearn by circumstance. It’s the old, successful organizations, the ones with the most “learning” encoded in their structures, that face the deepest unlearning challenge.

The Ones Who Will Thrive

If unlearning is the bottleneck, who gets through it? Not the smartest. We’ve established that raw intelligence faces diminishing returns and predicts neither wealth nor adaptation. The highest-IQ individuals may actually struggle more if they’ve over-invested in intellectual frameworks that no longer apply.

Not the most experienced. Deep experience cuts both ways. It provides judgment that novices lack. But it also creates chunked patterns and identity attachments that resist revision. The most experienced may face the deepest unlearning challenge.

The ones who will thrive share a different profile:

They hold knowledge lightly. They’ve learned without fusing identity with what they’ve learned. They can say “I was wrong” or “that’s obsolete now” without experiencing it as self-destruction. They treat expertise as a tool to be upgraded, not a possession to be defended.

They have clear intentions upstream of their capabilities. They know what they’re trying to achieve, independent of how they’ve historically achieved it. When the “how” becomes obsolete, they don’t lose their direction; they just swap methods. This is what Sam Altman means when he says “figuring out what questions to ask” will be more valuable than figuring out answers.

They’ve practiced unlearning before. Unlearning is a skill. Like any skill, it improves with practice. People who’ve navigated previous reinventions, career changes, industry shifts, and paradigm updates have developed the psychological muscle memory for letting go. They know what it feels like and that they can survive it.

They maintain peripheral vision. They pay attention to things outside their domain. They notice weak signals. They stay curious about fields that aren’t “relevant” to their current work. This peripheral vision provides early warning when their core expertise is becoming obsolete, and provides raw material for what comes next.

They prioritize clarity over competence. They’d rather be clear about the right problem than competent at solving the wrong one. This orientation means they’re constantly asking “Is this still the right question?” rather than “Am I getting better at answering this question?” When the questions shift, they shift with them.

The Question Underneath the Question

Bryan Johnson says intelligence costs are headed to zero. He’s describing the supply curve. But supply is only half of economics. The other half is demand — what people want, why they want it, and what they’re willing to give up to get it.

When intelligence was scarce, knowing what you wanted was relatively easy. The hard part was figuring out how to get it. Most of the business strategy, career development, and personal improvement was organized around the “how” problem. Acquire skills. Build knowledge. Develop expertise. Execute effectively.

When intelligence is abundant, the difficulty inverts. The “how” problem becomes trivial. AI can figure out how to do almost anything. The “what” problem becomes paramount. What do you actually want? What’s worth doing? What problem is worth solving?

These aren’t intelligence questions. They’re clarity questions. And clarity requires unlearning at least as much as learning.

You have to unlearn what you thought you wanted (because some of it was just pattern-matching to what seemed achievable). You have to unlearn what you thought was important (because some of it was just competitive positioning within a paradigm that’s shifting). You have to unlearn who you thought you were (because some of it was just identity fused with expertise that’s being commoditized).

The Terman study children weren’t held back by low intelligence. They were held back by something else — something the researchers didn’t measure and couldn’t name.

Maybe what they lacked was this: the ability to hold their considerable intelligence lightly, to point it at worthy problems rather than merely solvable ones, and to update what they knew when the world changed beneath them.

Maybe what they lacked was the capacity to unlearn.

The cost of intelligence is headed to zero. The cost of unlearning, of releasing what you know to make room for what you need, may be headed in the opposite direction.

That’s the real bottleneck. And it’s entirely human.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.