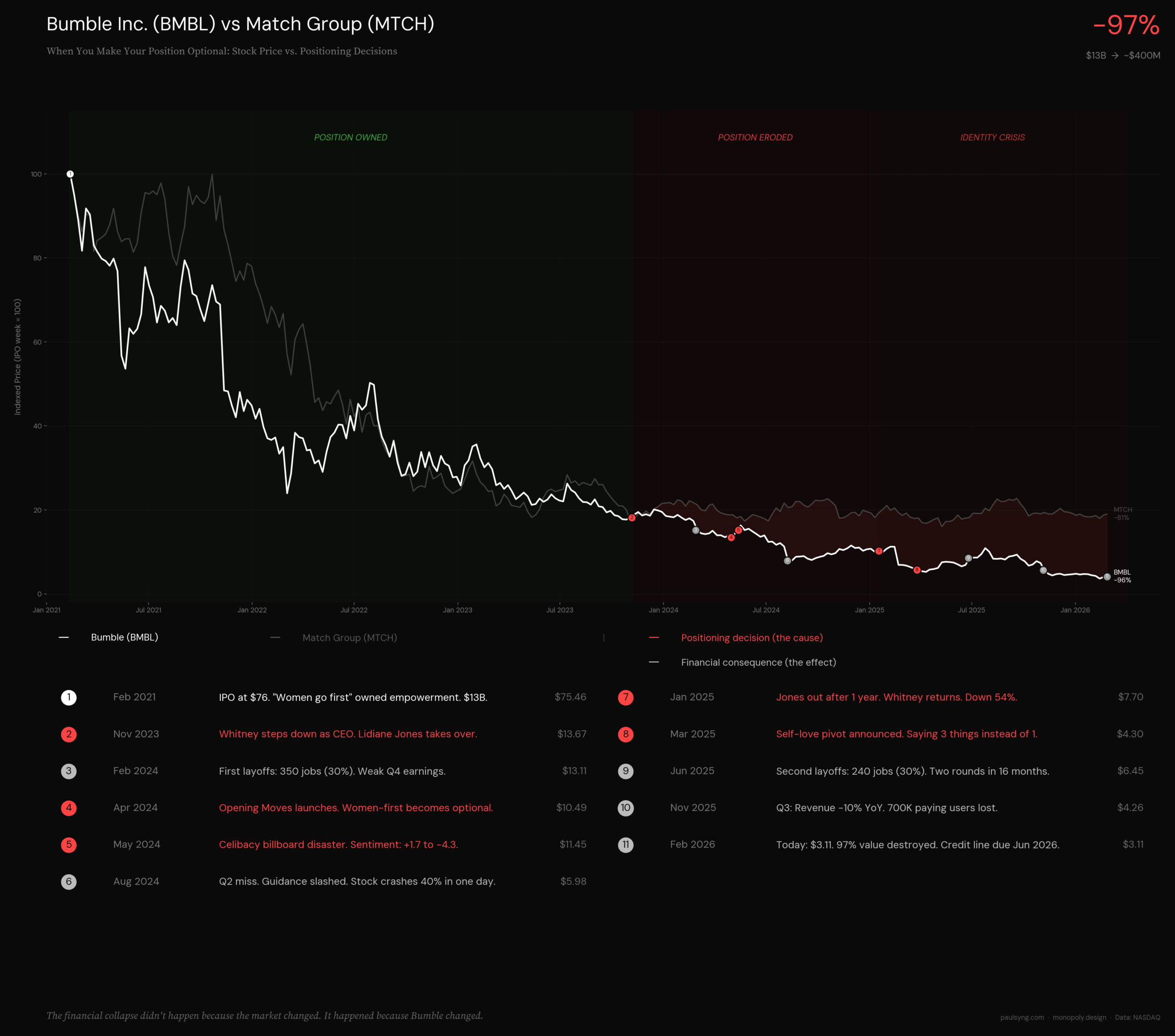

Today, we’ll dive into how a $13 billion company destroyed 97% of its value by abandoning the one thing that made it worth $13 billion.

The highlight reel, first.

Bumble had one job: be the dating app where women go first.

That single rule — women message first, men wait — wasn’t a feature. It was a belief system made tangible. It said something about what Bumble stood for, how relationships should begin, and who you were if you used it.

For eight years, that belief generated $13 billion in market value. Bumble became the third-largest dating platform in the world. Not because it had better technology. Not because it spent more on ads. Because it owned a concept in people’s minds: empowerment.

Then Bumble got restless. They made “women go first” optional. They pivoted toward “self-love.” They added manipulative tricks to squeeze more money from paying users. They started saying three different things about what they were.

Today, the company is worth roughly $400 million. That’s a 97% collapse from peak. Seven hundred thousand paying users left in the last twelve months alone. Revenue is falling faster each quarter. The credit line comes due in four months. And the company still can’t answer a basic question: What is Bumble?

This is the story of how it happened, what the numbers actually show, and the narrow path that could bring it back.

FYI. This is the 3rd and final leg in the series. Take a look at the first and the second, if you’re curious.

Part 1: What Bumble Actually Built

Whitney Wolfe Herd didn’t set out to build a dating app. She set out to fix a broken power dynamic.

After co-founding Tinder and leaving amid a sexual harassment lawsuit, she had a clear enemy: the toxic culture of online dating. The insight was simple. Harassment happens because dating apps replicate dating dynamics where men initiate, and women filter. Change the structure, change the behaviour. Give women the power to start the conversation, and you change the psychological contract of the entire interaction.

This is what made Bumble’s original positioning so powerful. It wasn’t claiming to be “safer than Tinder” or “better for women.” It owned the concept of empowerment itself. The women-first rule wasn’t a feature in a product comparison chart. It was proof of a different belief about how relationships should begin.

In positioning terms, Bumble owned a noun. Not an adjective like “safe” or “empowering,” a noun. Empowerment. When people thought about dating apps where women had agency, they thought of Bumble. That’s mental territory ownership. It’s the difference between describing what you do and owning what you mean.

The competitive landscape was clean:

Tinder owned casual discovery. High volume, low friction, spontaneous swiping. A functional position: here’s what you get.

Hinge owned relationship intent. “Designed to be deleted.” A functional position: here’s what you’re here for.

Bumble owned empowerment. Control over how the connection begins. A values position: here’s who you are when you use this.

That distinction matters more than it looks. Tinder and Hinge defined themselves by outcomes. Bumble defined itself by identity. When you chose Bumble, you were making a statement. Women said, “I deserve respect. I initiate on my terms.” Men said, “I’m comfortable with women leading.” It wasn’t about the app. It was about the person using it.

This created what’s called a perceptual monopoly. Once Bumble owned empowerment, competitors could only say “we’re empowering too,” which is an inherently weaker position because it accepts Bumble’s leadership as the reference point.

The architecture was elegant:

The noun was empowerment, specifically, female agency in connection.

The verbs were the product mechanics that proved it: women initiate conversations, matches expire in 24 hours, safety features reduce harassment, and quality filters maintain standards.

The genius was alignment. The noun and the verbs reinforced each other. The 24-hour expiry window wasn’t a growth trick. It manifested the belief that real connection requires intention. You had to act. You had to choose. The product forced the behaviour that proved the belief.

That alignment created four compounding advantages:

Concept ownership created pull. Bumble didn’t need to explain why empowerment mattered. The concept sold itself. People understood it instantly. Owning it created a gravitational force. Customers came to Bumble without being dragged there by advertising.

The product was the proof. Features weren’t separate from the mission. They were the mission made real. You couldn’t separate what Bumble did from what it stood for. This is rare. Most companies say one thing and build another. Bumble said empowerment and built empowerment.

Identity alignment drove loyalty. Users became advocates because using Bumble expressed their values. This created organic growth — word of mouth, social sharing, cultural credibility — that paid advertising can’t manufacture. People identified proudly as “Bumble users.” Few people proudly identify as Tinder users.

The position justified premium pricing. Values-based positioning meant users paid for principles, not pixels. That’s a stronger foundation for subscription revenue than feature comparison.

The business model worked because the positioning worked. Revenue grew. Margins expanded. The company went public in February 2021 at a $13 billion valuation, making Whitney Wolfe Herd the youngest woman to take a company public. She rang the bell with her baby on her hip.

Even the business model reinforced the position. Bumble ran a freemium model with paid tiers — Bumble Boost, Bumble Premium, and Bumble Premium+. Critically, no paid feature let men bypass the women-first rule. You couldn’t pay to skip the wait. Premium offered conveniences: see who liked your profile, extend an expiring match by 24 hours, and get unlimited swipes. The monetization respected the mental territory. Revenue didn’t contradict the belief system. This is rare. Most companies build business models that quietly undermine their positioning. Bumble’s model proved it.

The growth strategy was just as aligned. Instead of blasting ads, Bumble seeded college campuses with over 420 ambassadors by 2021. Growth happened through community, not performance marketing. People joined because someone they trusted said, “This one’s different.” The referral engine ran on values alignment, the most durable growth loop a company can build.

They expanded beyond dating with Bumble BFF for friendships and Bumble Bizz for professional networking. The logic was sound: if empowerment works for dating, it should transfer to other connection types. They advocated for legislation against cyberflashing. They partnered with the National Domestic Violence Hotline. They invested in female-founded startups through the Bumble Fund.

Every move reinforced the same concept. Bumble wasn’t just a product. It was a cultural force that happened to make money through subscriptions. The market didn’t value Bumble at $13 billion because it was a good app. It valued Bumble at $13 billion because it controlled mental territory that no competitor could credibly claim.

Part 2: Where They Lost It

Bumble made the classic mistake. They treated their position as a feature to be optimized instead of a belief to defend. This didn’t happen in one dramatic moment. It was a sequence of decisions, each rational in isolation, that collectively dismantled what made Bumble valuable.

Decision 1: Making the Rule Optional

In 2024, Bumble introduced a feature called “Opening Moves.” It allowed users to set conversation-starting questions that either person could respond to. In practice, it made “women message first” optional.

The stated logic was reasonable: reduce friction, give users flexibility, increase engagement metrics. The unstated consequence was devastating. Bumble turned its proof into a toggle. The one product mechanic that embodied its belief system became a setting users could switch off.

The market read this correctly. Brand sentiment scores crashed immediately. Consideration scores dropped. Customers understood the signal before Bumble did: “They never really meant it. It was a gimmick.”

In positioning terms, Bumble made its Level 4 ownership (the concept people associate with them) optional by making its Level 2 proof (the product behaviour that demonstrates the concept) optional. When your proof becomes optional, the position collapses. It’s like Volvo announcing that safety features are now an add-on package.

Decision 2: The Self-Love Pivot

In 2025, Whitney Wolfe Herd returned as CEO with a new vision: transform Bumble into “Duolingo for self-love and confidence building.” The app would include journaling, self-esteem exercises, AI-powered relationship coaching, and personal development tools. Dating would become one of many components.

The company acquired Geneva, an AI relationship coaching platform, to signal this direction. The positioning language shifted from “women-first dating” to “self-love platform” to “emotional intelligence.”

This is a founder projecting personal growth onto the company strategy. Whitney’s evolution from harassment survivor to empowerment advocate to self-love philosopher is genuine and admirable. But her personal journey and the company’s positioning are not the same thing.

Her identity needs: process trauma, evolve beyond victimhood, and explore holistic well-being.

Customer identity needs: find respectful connections without harassment or manipulation.

Those aren’t the same need. The self-love pivot serves the founder’s identity. It doesn’t serve the mental territory Bumble owns.

Worse, it puts Bumble at Level 1 (claiming) in a category where established players already operate at Level 4 (owning). Headspace owns mindfulness. Calm owns meditation. BetterHelp owns accessible therapy. You can’t skip from claiming a position to owning it. Each level builds on the one before it. Bumble would need five to seven years and hundreds of millions of dollars to maybe contest that territory. And even then, why would a dating app be the authority on self-love?

Meanwhile, they abandoned the territory they already owned, dating empowerment, which took a decade to build and which no competitor can credibly claim.

Decision 3: Dark Patterns

While claiming empowerment externally, Bumble implemented the opposite internally.

“Out of likes” manipulation. Multi-step cancellation flows designed to make quitting difficult. Guilt-inducing copy when users tried to downgrade. Artificial scarcity tactics. Visibility throttling that users describe as “rigged,” pay or disappear. Aggressive paywalling of features that used to be free. Premium tiers up to $199 focused on extracting maximum revenue from committed users.

Every manipulative nudge communicates the same thing: “We claim empowerment but practice extraction.”

Independent analysis scored Bumble’s alignment between what it promises and what customers actually experience at 1.0 out of 5.0. That’s not a gap. That’s a contradiction.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

Bumble says: “Women making the first move creates better connections.”

Customers say: “Most matches expire without messages or get a generic ‘hey’ opener.”

Bumble says: “Premium features enhance your dating success.”

Customers say: “I paid for three months and got exactly one date. It feels rigged.”

Bumble says: “Safer, higher-quality dating environment.”

Customers say: “Bots, scammers, and unfair bans without explanation.”

When the gap between promise and experience gets this wide, trust collapses. And when trust collapses in a business that depends on word-of-mouth and identity alignment, the organic growth engine doesn’t just slow down. It runs in reverse. Unhappy users don’t just leave, they warn others.

Decision 4: Saying Three Things Instead of One

Ask three people what Bumble is today, and you get three answers:

The website says, “Relationship platform.”

The CEO says, “Self-love app.”

Customers say, “Women-first dating app.”

Only one of those describes the mental territory Bumble actually owns. The other two are aspirations without foundation. When a company’s own website, CEO, and customers can’t agree on what it is, that company doesn’t have a messaging problem. It has an identity crisis.

Confusion always loses to clarity. Hinge knows what it is. Tinder knows what it is. Bumble no longer knows what it is. And the market is pricing that confusion accordingly.

Part 3: The Scoreboard

The financial data doesn’t explain why Bumble is failing. The positioning collapse explains that. But the numbers show how urgent this is.

Stock price

Bumble’s total company value has fallen from roughly $13 billion at its peak to roughly $400 million today. That’s a 97% destruction of shareholder value. The stock trades around $3.22 per share.

To put that in perspective: the company spent approximately $385 million buying back its own shares at an average price above $11. Those shares are now worth about $110 million. That’s $275 million in destroyed value — capital that could have funded four or more years of repositioning work.

Revenue

Annual revenue peaked at around $1.07 billion in 2024, only 2% higher than the previous year. Already barely growing. By the third quarter of 2025, revenue was $246 million, down 10% from the same quarter the prior year. The company’s forecast for the fourth quarter of 2025 is $216 to $224 million, 14% to 17% lower than the same quarter last year.

The important thing here is that the decline is accelerating, not stabilizing. Each quarter is worse than the last. The implied full-year 2025 revenue is roughly $960 million, meaning about $110 million in annual revenue has disappeared since the peak. That’s real money that isn’t coming back unless something fundamental changes.

Paying users

In the third quarter of 2024, Bumble had 4.3 million paying users. One year later, that number was 3.6 million. Seven hundred thousand paying users left in twelve months. That’s a 16% decline.

Revenue per paying user

Here’s where it gets interesting. Revenue per paying user actually rose 6.9% year over year to $22.64. That sounds like good news until you understand what it means. Bumble is charging more to its remaining users while failing to retain or attract new customers. They’re squeezing a shrinking base. This works for a quarter or two. Then it breaks, because the remaining users eventually leave too, especially when the price increases aren’t matched by improvements in their experience.

You can’t shrink your way to growth. This strategy inverts within two to three quarters.

Customer trust

Bumble’s Trustpilot score — where customers leave reviews voluntarily — is 1.9 out of 5. Sixty-four percent of all reviews are one star.

The independent Monopoly Perception Gap Analysis scored Bumble’s alignment between claims and customer experience at 1.0 out of 5.0.

That 1.0 means customers experience the opposite of what Bumble promises. This isn’t a marketing problem. It’s a trust crisis. When trust collapses, organic customer acquisition dies, and the cost to acquire each new customer explodes.

Cost structure

Bumble has done two rounds of layoffs, each cutting roughly 30% of the workforce, first in January 2024, then in June 2025. Combined restructuring costs were $33 to $38 million. Expected annual savings: about $40 million.

They’ve cut deep, twice. The savings are being reinvested in “product and technology.” But in service of what position? Execution without strategic clarity is just expensive experimentation. Spending $40 million on product development doesn’t help if you don’t know what you’re building toward.

Balance sheet

Total debt: $589 million.

Cash on hand: $308 million.

Net debt (what you owe minus what you have): approximately $281 million.

And here’s the critical detail: Bumble’s revolving credit facility (basically a line of credit the company can draw from) comes due in June 2026. That’s four months from now.

They’re refinancing during a revenue decline with a scattered strategic story. Lenders don’t just look at the numbers. They look at whether management has a coherent plan. “We’re pivoting to self-love” is not a coherent plan when your core business is shrinking 10-17% per quarter.

Part 4: What Customers Actually Say

Numbers measure the damage. Customer language explains it. When you listen to what Bumble users say on Reddit, Trustpilot, and review platforms, not in surveys, not when they know the company is listening, but when they’re talking to each other, a clear pattern emerges.

The pain

“My account was banned without any warning or explanation after I paid for a three-month subscription.”

“I’ve had Bumble Gold for three months, and I’ve gotten exactly one date.”

“It feels like Bumble decided they’d rather milk whales than actually help normal people date.”

“It’s like as soon as my Boost ran out, I disappeared. No new matches for days.”

“They automatically renewed my subscription for another six months without any clear reminder.”

The hope

“I just want to feel safe and in control when dating online.”

“I really liked the fact that I had the power to make the first move.”

“Bumble is the only app where my inbox doesn’t feel like a war zone.”

“I met my boyfriend on Bumble, and we’ve been together for over a year now. I really liked that I had to message first — it made me feel more in control.”

The self-inflicted wounds

Beyond the slow erosion, Bumble created acute crises. In 2024, they ran a billboard campaign featuring a woman abandoning nun vows for a shirtless gardener. The intent was playful. The effect was celibacy-shaming — mocking women who choose not to date. For a company that built its identity on respecting women’s choices, this was a direct contradiction.

Brand health scores (the measure of how positively people feel about the brand) plummeted from +1.7 to -4.3. Bumble had to publicly apologize. The damage wasn’t just the campaign. It was the signal: the people making decisions at Bumble no longer understand what Bumble stands for.

The pattern

Customers who love Bumble love it for the same reason: control and safety. Customers who are leaving are leaving for the same reason: the promise of control and safety is contradicted by the product experience.

Nobody is asking for self-love features. Nobody is asking for journaling or confidence exercises. They’re asking for Bumble to be what it claimed to be: a dating app where women have real agency, and the experience matches the promise.

The mental territory still exists. Customers still call Bumble a “women-first dating app.” The noun “empowerment” is still associated with Bumble in people’s minds. But it’s eroding, not strengthening. And every quarter that passes with dark patterns, confused messaging, and a self-love pivot nobody asked for accelerates that erosion.

Part 5: What Happens If Nothing Changes

If Bumble continues on its current trajectory, the math is predictable.

Within six months (by mid-2026): Revenue continues declining 10-15% per quarter. The paying user base drops below 3 million. Refinancing negotiations for the June 2026 credit line become significantly more expensive — lenders charge higher rates when they’re concerned about repayment. Employee morale craters as the self-love pivot shows no traction. The gap between what Bumble promises and what customers experience widens further.

Within twelve months (by the end of 2026): Full-year 2026 revenue falls below $850 million. Another round of layoffs becomes necessary. Trust scores drop below 1.5. Customer acquisition costs continue rising as the organic referral engine operates in reverse. Strategic options narrow, the company either sells at a distressed price or continues spiralling.

Within twenty-four months (by the end of 2027): The paying user base stabilizes around 2 to 2.5 million. Revenue run-rate settles at $650 to $750 million. The company is valued at $200 to $300 million — another 50% drop from today. Strategic value diminishes to the point where a sale becomes inevitable, likely at a fraction of what the business was once worth.

The cost of inaction: $150 to $200 million in additional company value destruction, plus the opportunity cost of the capital and time spent chasing territory Bumble will never own.

And this is happening while the dating market itself isn’t dying. Match Group (which owns Tinder, Hinge, and others) has stabilized. Hinge is specifically growing because it knows what it is and doubles down on that clarity. The problem isn’t the industry. The problem is Bumble.

Part 6: The Path Back

The good news: Bumble still owns something. Mental territory doesn’t vanish overnight. It erodes. Bumble is eroding, not gone. Customers still call it a “women-first dating app.” The noun is still theirs to reclaim. The path back isn’t complicated. It requires courage, not complexity.

Here are the five decisions that create 80% of the recovery.

Decision 1: Recommit to Women-First. Not as a Feature. As the Rule.

Make women-first messaging non-negotiable again. Not optional. Not a setting. The rule. This is the single mechanic that proves empowerment at scale. Every match that starts with a woman’s message reinforces the belief system. Every match that doesn’t undermine it.

Yes, some users will leave. They weren’t Bumble’s customers anyway. Bumble’s customers are people who believe relationships should start with mutual respect and intentional choice. Build for them. Positioning means accepting a narrower audience in exchange for deeper loyalty and pricing power.

Remove “Opening Moves” optionality. Reframe the 24-hour window as a feature, not a bug — it signals intention. Build premium features within the women-first framework: verified identities, community access, expert content, trust-building tools.

This stabilizes paying user churn by re-clarifying who Bumble is for. It justifies premium pricing by renewing the alignment between promise and experience. And it rebuilds the organic referral engine as advocates return.

Decision 2: Kill the Self-Love Pivot

Bumble doesn’t own self-love. It can’t skip from claiming it to owning it. Each level of positioning builds on the previous one. Bumble would need five to seven years and $300 to $500 million to maybe contest that territory against companies that already own it.

Bumble owns dating empowerment. If it wants to help with confidence, it should do it through connection — its actual expertise. Partner with therapists for therapy. Don’t try to become Headspace when you’re Bumble.

Cancel or pause self-love feature development. Reallocate the $40 million in restructuring savings to defending and deepening empowerment in the dating context. Reframe the messaging: the way you connect shapes how you feel. Bumble helps you connect with agency.

This stops burning capital in unowned categories, focuses investment on territory Bumble can defend, and removes the strategic confusion that’s paralyzing execution.

Decision 3: Remove Every Dark Pattern

Trust is the moat. Dark patterns are a leak in the moat. Every “you’re out of likes” prompt, every multi-step cancellation flow, every artificial scarcity tactic boosts quarterly metrics and destroys annual value. Bumble is optimizing for revenue per user at the expense of customer lifetime value and organic growth. The math breaks within 18 months.

Remove manipulative prompts and artificial scarcity. Make premium genuinely worth paying for—better curation, real safety improvements, community features, and trust-building tools. Rebuild moderation to match the safety promise. Users paying a premium expect premium curation.

This slows revenue-per-user growth in the short term — two to three quarters. But it stabilizes and then reverses churn by closing the perception gap. And it rebuilds trust scores, thereby reducing the cost of acquiring new customers.

Decision 4: Test BFF and Bizz. Keep Them or Kill Them.

Bumble owns empowerment in dating. Does that transfer to friendship? To professional networking? Test it. But stay within empowerment territory. If BFF succeeds, it’s because “women-first” dynamics create healthier friendships. If Bizz succeeds, it’s because empowered professional connections feel different than LinkedIn spam.

If they don’t prove that thesis, shut them down. Scattered product lines without unified positioning dilute everything. Measure whether BFF and Bizz actually benefit from the empowerment positioning or whether they just share an app shell. If they don’t reinforce the core position, sunset them. Reallocate resources to the core dating experience.

This eliminates complexity, focuses execution on the revenue engine that matters, and tests whether Bumble’s positioning has legs beyond dating without betting the company on it.

Decision 5: Say One Thing

Stop saying three things. Say one thing.

Not “relationship platform” (too generic).

Not “self-love platform” (Bumble doesn’t own it).

Not “the love company” (vague).

“Bumble: Where women go first.”

That’s it. The message and the mechanic are the same. If someone asks what Bumble does, every employee should say the same seven words.

Rewrite the website, marketing, investor materials, and internal documents to align on one position. Train every employee to articulate it in one sentence. Make positioning clarity a board-level metric — track internal and external alignment quarterly.

This reduces wasted marketing spend on scattered messages. It clarifies acquisition targeting, Bumble knows exactly who it’s for. And it rebuilds brand coherence, which compounds over time.

Part 7: The Belief Shift

None of this works without changing what Bumble believes internally.

Old belief: “Women-first was a feature. We need to evolve beyond it to grow.”

New belief: “Women-first is our position. Defending it is how we grow.”

Old belief: “We need to expand into wellness to unlock new revenue.”

New belief: “We need to own empowerment deeper to justify premium pricing in the category we already dominate.”

Old belief: “Competitors are winning by offering more features.”

New belief: “Competitors win by owning clear positions. We beat them by defending ours, not copying theirs.”

Old belief: “Dark patterns are necessary to hit quarterly revenue targets.”

New belief: “Dark patterns destroy trust, which destroys the premium we can charge and the organic referrals we need. Short-term revenue games kill long-term value.”

Old belief: “Positioning is marketing’s job.”

New belief: “Positioning is the CEO’s job. It shapes product, pricing, hiring, capital allocation, and every board conversation.”

Part 8: The Timeline

Now (Q1 2026): Decide. Are we doing this? If yes, announce the recommitment to women-first. Internal memo first. External second. Remove Opening Moves optionality from the product roadmap. Kill or pause all self-love platform features. Begin dark pattern audit.

Q2 2026: Launch the cleaned-up product experience. No dark patterns. Refinance the credit line with a clear, coherent strategic narrative — lenders respond to clarity. Start rebuilding trust with a public commitment to safety and moderation improvements. Measure early signals: Is churn slowing? Are trust scores moving? Is brand sentiment improving?

Q3–Q4 2026: Double down on what’s working. Premium features that actually empower. Test the BFF and Bizz transfer hypothesis — keep or kill based on data. Rebuild marketing around one clear message. Target: revenue decline slows to 5% or less.

2027: Target: return to revenue growth (low single digits is fine, it proves the thesis). Target: paying user growth, even 2-3%. Target: trust score recovery to 2.5 or above out of 5. Target: stock recovery to $6-8 range. Still well below the peak, but more than double from today.

Part 9: Why This Matters Beyond Bumble

Bumble’s story isn’t unique. It’s a pattern. A company builds something valuable by owning a clear concept. It works. Growth comes. The market rewards it. Then leadership gets restless. The original idea feels limiting. Expansion beckons. Someone says, “We need to evolve” or “we need to be more than just X.”

So they soften the position. They chase adjacent categories. They dilute the message. They add features that contradict the original belief. And slowly, the thing that made them valuable stops being the thing they invest in.

The financial collapse didn’t happen because the market changed. It happens because the company changed, and changed in a direction that weakened the only thing competitors couldn’t copy.

The lesson is counterintuitive: the path to growth isn’t expansion. Its depth. Own something so completely that no competitor can credibly challenge you for it. Make every decision (product, pricing, culture, communication) reinforce that ownership. Accept that not everyone will be your customer. That’s a feature, not a bug.

The founder trap is particularly dangerous. Founders who build mission-driven companies often conflate their own personal evolution with the company’s strategic direction. Whitney’s growth as a person is real and admirable. But a company’s positioning lives in customers’ minds, not in the founder’s journal. The question isn’t “What does the founder want to become?” It’s “What does the company own in customer minds, and how do we defend it?”

There’s also a broader lesson about the relationship between features and beliefs. When Bumble made “women go first” a feature, it could be copied, adjusted, or turned off. When it was a belief, it was the foundation on which everything else stood. Features are tactical. Beliefs are structural. The moment you treat a belief as a feature, you’ve already lost it.

Whitney herself admitted something remarkable in 2021: “The brand is better than the product right now.” That was the clearest possible warning. The position was strong, but the experience was falling behind. The right response was obvious: make the product match the brand. Close the gap between what Bumble promises and what customers actually get.

Instead, they did the opposite. They changed the brand to match a vision nobody asked for. They moved the goalposts rather than reaching them. And the market, which is just millions of individual people making individual decisions, noticed.

Bumble’s original position was rare. Most companies never achieve mental territory ownership at all. Bumble did. They owned empowerment in dating. That position was worth $13 billion.

Then they made it optional.

The Choice

Bumble has two options.

Option A: Keep doing what they’re doing. Revenue declines another 10-15% in 2026. They cut staff again. They try another pivot. The stock drifts toward $2. Strategic options narrow. They sell at a distressed valuation or spiral further.

Option B: Defend the territory they own. Recommit to women-first. Kill the self-love distraction. Remove the dark patterns. Say one thing. Rebuild trust. Accept 12-18 months of hard, focused execution before the market rewards it.

Option A is a slow death.

Option B is survival, then growth.

The market didn’t take $12 billion from Bumble because dating apps are dying. Match Group has stabilized. Hinge is growing. The market took it because Bumble stopped defending what it owned.

The opportunity isn’t self-love. The opportunity is being the definitive answer to a question that matters: “How should people connect with respect and agency?”

Bumble already owned that question.

They just need to stop making the answer optional.

PS: Bumble (or Whitney) built something rare. The question is whether they have the courage to stop throwing it away.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.